A FASCINATING directory for the city of Londonderry – dating from the early nineteenth century – has been newly-published on the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) website, offering a rich insight into what it would have been like to live there one hundred and seventy years ago.

A FASCINATING directory for the city of Londonderry – dating from the early nineteenth century – has been newly-published on the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) website, offering a rich insight into what it would have been like to live there one hundred and seventy years ago.

A New Directory of the City of Londonderry, 1839, paints a vivid portrait of the town just years prior to the Great Famine, when William Lamb was Queen Victoria’s Prime Minister and Hugh Fortescue was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

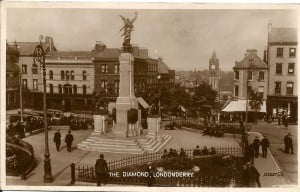

The old tome describes what was once a bustling centre of international commerce. Citizens could buy a range of local snuffs and West Indian cigars in William Smith’s of The Diamond, hobnob with a range of international consuls in the King’s Arms in Pump Street, and then rub shoulders with the famed shipbuilder William Coppin, who captained the Robert Napier Steam-Packet, between the city and Liverpool every Friday.

The whole gamut of civic society is covered by the directory, appropriately enough for “the capital of the County,” a city of “very great antiquity” and “a place mentioned in history at so early a period as 546, at which time St Columb founded an Abbey here for Augustinian Canons.”

Readers of the directory can easily imagine the local notables and holders of high office alongside the flaxspinners and public houses of the Cowbog and the butchers of the shambles.

Political life is, of course, covered and we learn that the city had just one double-jobbing Alderman in 1839. That was MP Sir Robert A. Ferguson, who is today immortalised as the “Black Man” of Brooke Park, a statue that formerly stood in The Diamond.

Ferguson was joined on the Londonderry Corporation by Mayor Sir Robert Bateson and ten other Aldermen, just three of whom had not served as Mayor before.

Ferguson was joined on the Londonderry Corporation by Mayor Sir Robert Bateson and ten other Aldermen, just three of whom had not served as Mayor before.

John Nicholson, John Scholes and Joseph Ewing Miller were yet to accept the burden of the chains of office. But John Dysart, Richard Young, Conolly Skipton – the aforementioned Sir Robert A. Ferguson, Bart, MP – William Boyd, Joshua Gillespie, George Hill, and Thomas P. Kennedy had already endured the heavy responsibilty, the directory tells us. The Sheriffs of the day were listed as Thomas Know and Thomas Chambers whilst the Lord Bishop Richard Ponsonby presided over a 132 strong list of the local nobility, gentry and clergy – your reporter’s surname is unaccountably absent from this illustrious index.

Unemployment did not appear to be much of a problem at the time, the city boasting a bustling dock and city centre. Over 600 different trade and merchant enterprises were listed – some of which would have employed a large staff.

As the directory reads: “There are also an excellent shambles, and a good fish market, both well supplied.”

Well-supplied certainly. An army of 51 butchers attended the shambles led by William Doherty “Lessee and Clerk of the Butcher’s market.”

Market days were on Wednesday and Saturday with fairs on June 17, September 4 and October 17. A buttermarket was situated in Waterloo Place where Hugh Corbett was weighmaster and Richard Todd his deputy. Seventeen egg, fowl and butter shippers and four meal and flour dealers might have been found there of a market day.

And drink wasn’t a problem in those days. At least insofar as it came to getting your hands on it anyway. There were 116 registered publicans – 14 in the Cowbog, 12 in Shipquay and 9 in the Waterside.

Bibulous burghers of the day could depend on no fewer than nine wine and spirit merchants, three distillers and maltsters and two brewers. There were also 60 grocers throughout the city, some of whom were also spirit sellers – a nineteenth century version of the off sales. Hopefully eight surgeons and apothecaries in the town would have had the good sense not to flog ether to citizens for recreational use, although this became popular in the city later in the century – the air at the local railway station was at one stage reputed to have been thick with the odour of the anaesthetic agent.

Abstinent folk were also catered for by Richard Moore’s Soda Water and Ginger Beer operation in Ferryquay Street and by three tea-dealers listed in the book. The city’s environs are described in complimentary terms by the directory: “The streets within the gates are spacious, well-paved, lighted and cleaned; the houses in general are handsome and built of brick.

“The Diamond, a large handsome square in the centre of the city, adds greatly to is beauty; in the middle is the Exchange, a fine stately building.

“The Cathedral, which stands on high ground, is a grand Gothic structure, with a lofty square tower containing eight fine-toned bells; it is furnished with a good organ, and was built in 1633, under the inspection of Sir John Vaughan; and the tower has a fine effect when viewed at a short distance.

“The new Court-House, of which too much can scarcely be said, was built from an Athenian model, furnished by Mr Boden, of the finest stone, and in the most chaste style of architecture; in the central front is a grand portico, supported by four massy fluted pillars, on the top are the King’s Arms, on one side the emblematical figure of Mercy, and on the other that of Justice finely sculptured in stone; in fact, the entire edifice is an elegant display of taste and grandeur.”

It is also clear the literati were well-served with seven printers and letterpresses. And in Pump Street William Wallen presided over the history-stepped paper, cheek-by-jowl with his colleague Thomas McCarter of the Londonderry Standard. Edward Hyslop’s Londonderry Journal was in Shipquay Street. Six libraries and newsrooms were also frequented by literature lovers.

It is also clear the literati were well-served with seven printers and letterpresses. And in Pump Street William Wallen presided over the history-stepped paper, cheek-by-jowl with his colleague Thomas McCarter of the Londonderry Standard. Edward Hyslop’s Londonderry Journal was in Shipquay Street. Six libraries and newsrooms were also frequented by literature lovers.

If there was a serious falling out between local newspapermen you could in those days buy guns from William Cromie of Wapping, Joseph Love of Fountain Street and Francis G. Rogers of Bridge Street. Alternatively – as demanding satisfaction by duel was by this time falling out of fashion in Ireland – they could have purchased a few habana puros or a quantity of Lundy Foot’s High Toast Irish snuff from William Smith’s of The Diamond before adjourning to any one of a number of respectable establishments for a civilised tête-à-tête.

Likely meeting places would have been Jamieson’s Hotel, Campbell’s Hotel and the White Hart of Foyle Street, the City Hotel and Floyd’s Hotel of Shipquay Street, the King’s Arms of Pump Street and the Tirkeeran Arms of the Waterside.

Messrs Wallen, McCarter and Hyslop – as newspapers editors and proprietors – had a choice of banks in which to keep all their money.

The Agriculture and Commercial Bank of Ireland, Bank of Ireland, Provincial Bank of Ireland and Belfast Banking Company were all based in Shipquay Street. The Northern Banking Company was based in nearby Magazine Street.

A strong maritime heritage is also in evidence. Eleven master mariners, eight shipowners – S and J. Alexander, Danie Baird, James Corscadden, John Cooke, John Kelso, William McCorkell, R and W.F. McIntire and John Munn and four shipbrokers all contributed to what must have been an industrious quayside.

Two shipbuilders were also resident in the Londonderry of the day, including the famed William Coppin, engineer, ironfounder, boiler maker and captain of the Robert Napier, which sailed between the city and Liverpool weekly. Daniel McDonnell was the other.

According to the Ulster Biography William Coppin launched his first ship “City of Derry” in 1839 and the Londonderry Corporation presented Captain Coppin with an inscribed silver service.

Two years after the New Directory was published Coppin’s Great Northern – the largest ship of its kind in the world – was driven by an Archimedean screw propeller and in 1843 was berthed at the East India Inner Dock. Coppin next turned to salvage work and was elected a town councillor. In the 1880s he designed and built a triple-hulled iron ship, the Tripod Express which sailed the Atlantic. He was also to invent the artificial light fish-catching apparatus in 1886 and by the mid-nineteenth century employed five hundred men.

Coppin’s Robert Napier sailed to Liverpool every Friday from the Quay whilst the Isabella Napier sailed on a Tuesday. Other Steam-Packets sailed to Glasgow – The Antelope sailed on a Friday calling at Portrush, Greenock and Campbelltown; The Rover, St Columb and Foyle sailed on a Tuesday and a Thursday. And the fact that of thirteen bakers in the city many sold Ship Biscuits tells its own story.

How many stocked up before arduous journeys across the Atlantic? How many left the Quay on coffin ships in the wake of a famine ten years later that would utterly transform the demographic landscape of the country? Seafaring is described at length in the New Directory: “There is also six steam-boats attached to the port, by which passengers, as well as goods are conveyed to Liverpool, Glasgow and Campbelltown.

How many stocked up before arduous journeys across the Atlantic? How many left the Quay on coffin ships in the wake of a famine ten years later that would utterly transform the demographic landscape of the country? Seafaring is described at length in the New Directory: “There is also six steam-boats attached to the port, by which passengers, as well as goods are conveyed to Liverpool, Glasgow and Campbelltown.

“The extensive ship building establishment of Mr Coppin also deserves particular notice. Here a patent slip had been constructed for vessels of small burden; but by this gentleman’s improvements, it is being enlarged so as to admit of vessels from five tons to six hundred tons register.

“There is also an extensive foundry, and steam boiler manufactory; and steam engines for vessels of every class are constructed on the premises.” All this maritime activity established the city as an international port of some significance. A Vice-Admirality Office in Shipquay Street was inhabited by Charles Stewart, who acted as Consul to Sweden, Norway, and Prussia. Colleagues of Stewart’s included the Dutch Consul William Davenport and the United States Consul James Corscadden.

Meanwhile, a shirt industry that would later serve to illustrate the factory system in Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, was just kicking into gear in Londonderry at this time. Twenty-one haberdashers and linendrapers, three flaxspinners and 13 woollendrapers suggest a burgeoning linen and textile industry.

And it is also know that in 1831 – just years before the New Directory was compiled – William Scott of Balloughry – seeing an increased demand in Britain – got his wife and daughters to manufacture a number of shirts with which he boarded the aforementioned Steam-Packet, the Foyle, for sale in Glasgow.

The youth of the day also required an education and the Derry Diosecan School “usually called Foyle College” was principal. “A beautiful, modern and tastefully finished building,” notes the directory, “with suitable accommodation for eighty boarders.” “There is a very valuable Library attached to the School, as well as an Exhibition Fund. The pupils of this institution have been very lately successful in Trinity College, Dublin, obtained several first rank honours. ” Head Master at Foyle back in those days was Rev. William Smyth.

Other school teachers registered in the city were – Emma Bartowski (Ladies Boarding and Day, Mall Wall), John Bartowski (Teacher of Languages, Mall Wall), Rev. G.T Ewin (Classical teacher, East Wall), Matilda Hughes (Ladies’ Day, London Street), and John Gaston Leathem, (Private Teacher, Cunningham’s Row).

There were also the Infants’ Free School, Infants’ Day School, Independent Infant School, St Columb’s National School and a City Missionary, Andrew Jordan of Bennet’s Lane.

Gwynn’s Charity is also listed. Named after Muff-born philanthropist John Gwynn – who left £40,000 to build an orphanage and school for boys from Derry and Muff when he died in 1829 – it was opened opened in 1832 in Shipquay Street after an outbreak of Cholera. In the year the New Directory was published the Lord Bishop Richard Ponsonby laid the foundation stone of a new building in what is now Brooke Park following a great ceremony on Monday, September 9.

Londonderry had any number of amenities at this time including a Post Office in Richmond Street, the Custom House – with its own Inspecting Officer of Emigration, a Ballast Office with four master pilots and Mr Michael McMullen as Quaymaster, an Excise Office, a Stamp Office, a Consistoriol Court, the City and County Gaol, the City and County Infirmary and Fever Hospital and the Londonderry District Lunatic Asylum with served Derry, Donegal and Tyrone.

Additionally, Lieutenant General, the Right Hon. Lord Strafford was Governor of Londonderry and Culmore Fort and Chief Constable of the local constabulary was Francis Hamilton Nesbitt.

A list of Commisioners for Draining and Embanking Lough Foyle under a Special Act of parliament and a list of Poor Law Guardians are also mentioned in the directory. The Derry Workhouse would open in 1840 the following year. Freedom of movement and communication to and from the city was also guaranteed on land as well as by sea. Although the railway would not reach Londonderry until 1845 a frequent coach, carriage and mail service was in operation in 1839.

Coaches to Belfast, Dublin, Enniskillen, Omagh and Sligo departed regularly from the Coach Office in Foyle Street; cars and mail cars left for Belfast, Coleraine, Buncrana, Moville, Letterkenny and Strabane every day except Sunday; and carriers to Dublin, Belfast, Sligo and all other parts of Ireland, were operated by Joseph McLaughlin of William Street, William Doherty of Shipquay and William McMenemy of Bishop Street.

A further flavour of life in Londonderry at the time can be savoured through a range of other trades and merchants, which are mentioned in the New Directory. They are worth listing for their colour and because so many have now become obsolete due to plummeting revenues and efficiency savings over the years.

There once were nine agents, one architect, 14 attorneys and scriveners, six auctioneers, two ironfounders, seven ironmongers and hardware dealers, 10 leathercutters, 11 black and whitesmiths, two blockmakers, four bookbinders, four booksellers and stationers – possibly more than there are today? 11 boot and shoemakers, four braziers, brassfounders and tinsmiths, 10 cabinet makers and upholsters, two cardmakers, 14 carpenters and builders, 18 clothes brokers, two coachbuilders, seven coal dealers, three confectioners, three coopers, two corkcutters, two dyers, five earthenware and glass dealers, thirteen fire and life insurance companys, nine grain merchants, , four hatters, 27 merchants, 13 milliners and dressmakers, two nursery and seedsmen, nine oil, paint and colour dealers, 10 painters and glaziers, six pawnbrokers, eight physicians, one perfumer and haircutter – plenty of work for Daniel Watson of Shipquay Street – three plasterers, four plumbers and braziers, two rag and feather dealers, two rope makers, six saddlers and harness makers, two sailmakers, four salt manufacturers and limeburners, three silversmiths and jewellers, two skinners, six straw bonnet makers, two surveyors, 13 tailors, six tallow-chandlers and soapmakers, six tanners, three timber merchants, four tobacco manufacturers, two turners, seven watch and clockmakers, six window glass importers, , one leather merchant, one spade and shovel maker, one bandbox maker, one lathrender, one cutler, one stonecutter and Marble Mason, an unspecified number of staymakers and a millwright.

There once were nine agents, one architect, 14 attorneys and scriveners, six auctioneers, two ironfounders, seven ironmongers and hardware dealers, 10 leathercutters, 11 black and whitesmiths, two blockmakers, four bookbinders, four booksellers and stationers – possibly more than there are today? 11 boot and shoemakers, four braziers, brassfounders and tinsmiths, 10 cabinet makers and upholsters, two cardmakers, 14 carpenters and builders, 18 clothes brokers, two coachbuilders, seven coal dealers, three confectioners, three coopers, two corkcutters, two dyers, five earthenware and glass dealers, thirteen fire and life insurance companys, nine grain merchants, , four hatters, 27 merchants, 13 milliners and dressmakers, two nursery and seedsmen, nine oil, paint and colour dealers, 10 painters and glaziers, six pawnbrokers, eight physicians, one perfumer and haircutter – plenty of work for Daniel Watson of Shipquay Street – three plasterers, four plumbers and braziers, two rag and feather dealers, two rope makers, six saddlers and harness makers, two sailmakers, four salt manufacturers and limeburners, three silversmiths and jewellers, two skinners, six straw bonnet makers, two surveyors, 13 tailors, six tallow-chandlers and soapmakers, six tanners, three timber merchants, four tobacco manufacturers, two turners, seven watch and clockmakers, six window glass importers, , one leather merchant, one spade and shovel maker, one bandbox maker, one lathrender, one cutler, one stonecutter and Marble Mason, an unspecified number of staymakers and a millwright.

The last word should be left with the directory’s author who describes this picturesque city in terms, some of which are still recognisable today.

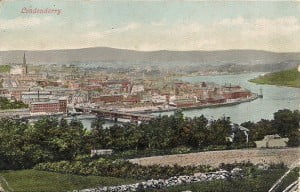

“The walls, gates and some of the bastions, which enclosed the old city are still entire, and are its most ancient remains, placed on an oval hill, which rises to a height of 119 feet, and washed by the Foyle, here a tidal river of more than a furlong in breadth.

“The view of the old city from the Waterside is very striking. The walls, although built in the year 1617, are in perfect repair, and from a fashionable and picturesque promenade,” the author notes.

“There are also an excellent shambles, and a good fish market, both well supplied. Across the river is a wooden bridge that deserves particular mention, constructed by Mr Samuel Cox of Boston, North America.

“This wonderful structure is 1068 feet in length and 40 in width, with a broad parapet on both sides for foot passengers. It is lighted by 26 lamps; at about a third of its length is a fine turning bridge, with very ingenious machinery, to admit vessels through. “The water that supplies the city is carried across this extensive bridge in metal pipes; indeed taken together it is an elegant, curious and wonderful erection.”

New Directory of the City of Londonderry, 1839 was published online by PRONI alongside a range of street directories from 1819 to 1900. The new online service contains over 29 directories, approximately 20,000 pages, and covers Londonderry, Belfast and provincial towns in Northern Ireland and in counties Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan from 1819 to 1900.

The directories contain a wide range of information about people, places and organisations and are an extremely useful source for all kinds of research such as tracing the location of a particular person or checking when a firm was in business. You can also search your own address to find out who lived there many years ago.

The directories can be accessed on the PRONI website.

From the Londonderry Sentinel Sept 2009